Body

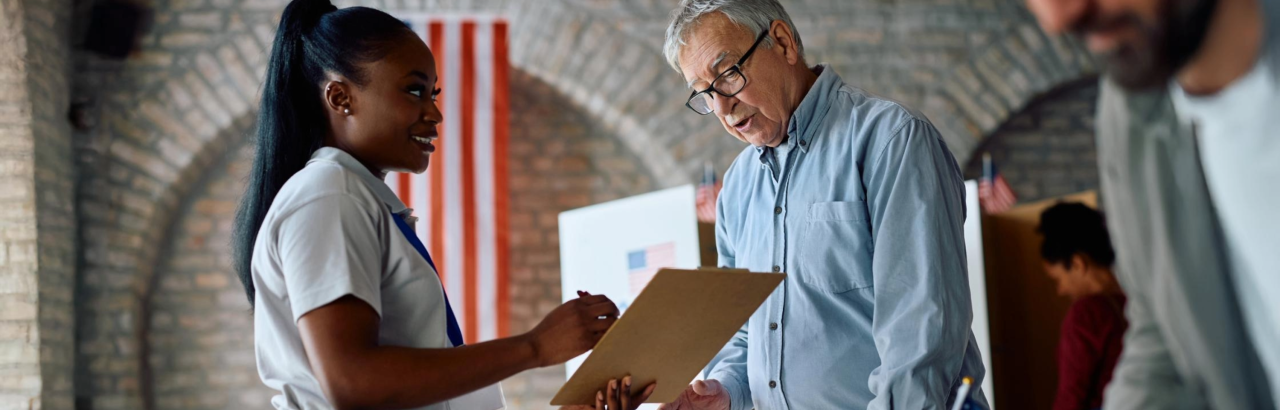

Picture a typical election day: standing in line at the polling place, confirming your voter information, following instructions from poll workers, and reading the ballot. After all these steps, finally the ballot is cast. Or, for others, it might entail casting votes at home, curled up with a warm cup of tea.

Although many people may take the voting process for granted, individuals with communication disabilities may face significant barriers to exercising their constitutional right to vote. Communication disorders (e.g. aphasia, apraxia and dysarthria, etc.) may impact individuals’ ability to communicate with election officials or interfere with their ability to read written text on a ballot.

“Speech and language are embedded into so much of the voting process,” said Laura Kinsey, MS, research speech-language pathologist at Shirley Ryan AbilityLab. “For people who experience communication disabilities, it’s useful to make an accessibility plan ahead of time and advocate for themselves in order to vote successfully.”

Kinsey, fellow speech-language pathologist Katie Wydra, and members of the Speech-Language Pathology Cultural Diversity, Inclusion, and Anti-Racism (SLP-CDIAR) Task Force at Shirley Ryan AbilityLab, have collaborated to provide voting resources for people with communication disabilities.

SLP-CDIAR developed “Make Your Vote Count,” a flyer with facts about the difficulties people with communication disabilities may face when voting and available resources to help. This flyer was created to highlight National Disability Voting Rights Week established by the American Association of People with Disabilities’ REV UP Campaign. Individuals living with communication challenges also have shared tips for how to make the voting experience a success, including:

Before Voting

Body

- Make a plan. Online checklists, like this example, are available to help people with communication disabilities plan out all steps of the voting process, such as deciding to vote in person or by mail; identifying accommodations; and having resources readily available if they experience issues while voting.

- Research accommodations. For example, some states and polling places offer plain-language ballots (available in 21 states); screen readers in which the ballot is read aloud with headphones; computer touch screens; or special marking devices and digital pens.

- Consider voting by mail. Voters can take their time completing the ballot from the comfort of their home.

- Have assistance. If voting in person, voters can choose a trusted family member, friend or other individual to assist them at their polling place, including helping them complete a ballot.

At the Polling Place

Body

- Bring identification and/or an information card that explains the communication disorder and strategies that might be most helpful for voting.

- Ask poll workers to speak slowly and repeat information as needed.

- Print out a list of voting choices and take it to the polling place to help guide ballot completion.

- Don’t feel pressured or rushed in the voting booth — it’s ok to take the time required to be thorough.

“Overall, it’s important to recognize that just because a voter may have difficulty speaking, it does not mean they lack the capacity to vote,” said Wydra. “All registered voters have the right to vote, and they are entitled to accommodations regardless of their communication status.”